[269]

CHAPTER VI.

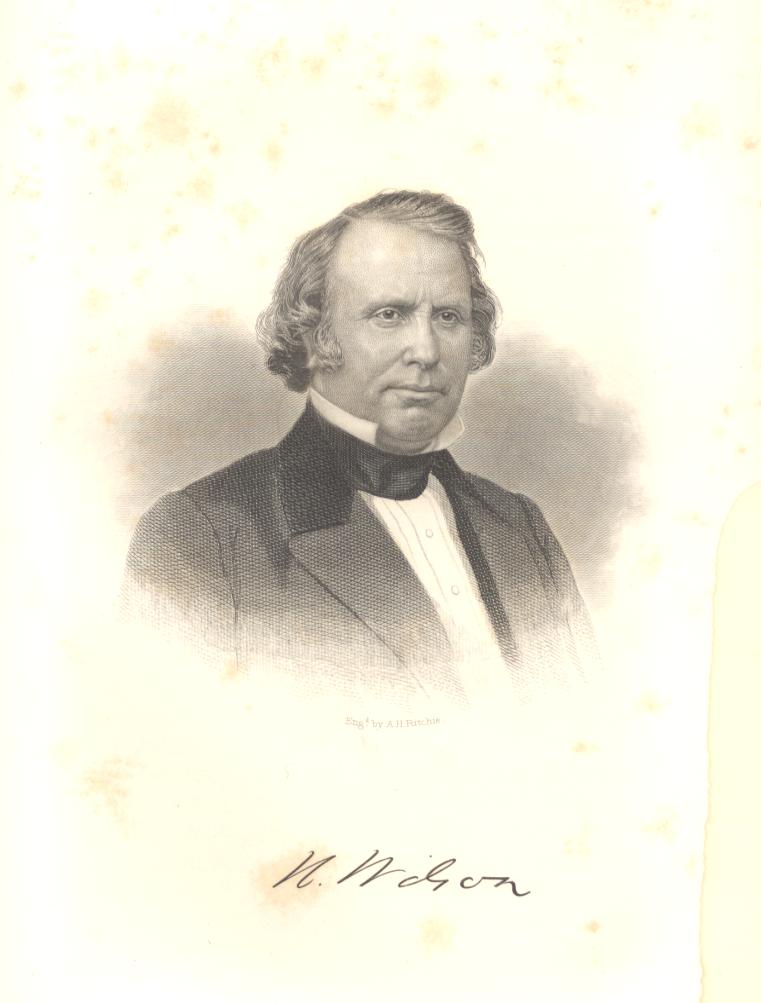

HENRY WILSON.

Lincoln, Chase and Wilson as Illustrations of Democracy—Wilson’s Birth and Boyhood—Reads over One Thousand Books in Ten Years—Learns Shoemaking—Earns an Education Twice Over—Forms a Debating Society—Makes Sixty Speeches for Harrison—Enters into Political Life on the Working-Mens’ Side—Helps to form the Free Soil Party—Chosen United States Senator over Edward Everett—Aristocratic Politics in those Days—Wilson and the Slaveholding Senators—The Character of his Speaking—Full of Facts and Practical Sense—His Usefulness as Chairman of the Military Committee—His “History of the Anti-Slavery Measures in Congress”—The 37th and 38th Congresses—The Summary of Anti-Slavery Legislation from that Book—Other Abolitionist Forces—Contrast of Sentiments of Slavery and of Freedom—Recognition of Hayti and Liberia; Specimen of the Debate—Salve and Free Doctrine on Education—Equality in Washington Street Cars—Pro-Slavery Good Taste—Solon’s Ideal of Democracy Reached in America.

It is interesting to notice how, in the recent struggle that has convulsed our country and tried our republican institutions, so many of the men who have held the working oar have been representative men of the people. To a great extent they have been men who have grown up with no other early worldly advantages than those which a democratic republic offers to every citizen born upon her soil. Lincoln from the slave states, and Chase and Henry Wilson in the free, may be called the peculiar sons of Democracy. That hard Spartan mother trained them early on her black broth to her fatigues, and wrestlings, and watchings, and gave them their shields on entering the battle of life with only the Spartan mother’s brief—“With this, or upon this.”

[270]

Native force and Democratic institutions raised Lincoln to the highest seat in the nation, and to no mean seat among the nations of the earth; and the same forces in Massachusetts caused that State, in an hour of critical battle for the great principles of democratic liberty, to choose Henry Wilson, the self-taught fearless shoemaker’s apprentice of Natick, over the head of the gifted and graceful Everett, the darling of foreign courts, the representative of all the sentiments and training which transmitted aristocratic ideas have yet left in Boston and Cambridge. All this was part and parcel of the magnificent drama which has been acting on the stage of this country for the hope and consolation of all who are born to labor and poverty in all nations of the world.

Henry Wilson, our present United States Senator, was born at Farmington, N. H., Feb. 12, 1818, of very poor parents. At the age of ten he was bound to a farmer till he was twenty-one. Here he had the usual lot of a farm boy—plain, abundant food, coarse clothing, incessant work, and a few weeks’ schooling at the district school in winter.

In these ten years of toil, the boy, by twilight, firelight, and on Sundays, had read over one thousand volumes of history, geography, biography and general literature, borrowed from the school libraries and from those of generous individuals.

At twenty-one he was his own master, to begin the world; and in looking over his inventory for starting in life, found only a sound and healthy body, and a mind trained to reflection by solitary thought. He went to Natick, Mass., to learn the trade of a shoe-

[271]

maker, and in working at it two years, he saved enough money to attend the academy at Concord and Wolfsborough, N. H. But the man with whom he had deposited his hard earnings became insolvent; the money he had toiled so long for, vanished; and he was obliged to leave his studies, go back to Natick and make more. Undiscouraged, he resolved still to pursue his object, uniting it with his daily toil. He formed a debating society among the young mechanics of the place; investigated subjects, read, wrote and spoke on all the themes of the day, as the spirit within him gave him utterance. Among his fellow-mechanics, some others were enkindled by his influence, and are now holding high places in the literary and diplomatic world.

In 1840, young Wilson came forward as a public speaker. He engaged in the Harrison election campaign, made sixty speeches in about four months, and was well repaid by his share in the triumph of the party. He was then elected to the Massachusetts Legislature as representative from Natick.

Having entered life on the working man’s side, and known by his own experience the working man’s trials, temptations and hard struggles, he felt the sacredness of a poor man’s labor, and entered public life with a heart to take the part of the toiling and the oppressed.

Of course he was quick to feel that the great question of our time was the question of labor and its rights and rewards. He was quick to feel the “irrepressible conflict,” which Seward so happily designated, between the two modes of society existing in America, and to know that they must fight and strug-

[272]

gle till one of them throttled and killed the other; and prompt to understand this, he made his early election to live or die on the side of the laboring poor, whose most oppressed type was the African slave.

In the Legislature, he introduced a motion against the extension of slave territory; and in 1845, went with Whittier to Washington with the remonstrance of Massachusetts against the admission of Texas as a slave State.

When the Whig party became inefficient in the cause of liberty through too much deference to the slave power, Henry Wilson, like Charles Sumner, left it, and became one of the most energetic and efficient organizers in forming the Free Soil party of Massachusetts. In its interests, he bought a daily paper in Boston, which for some time he edited with great ability.

Meanwhile, he rose to one step of honor after another, in his adopted State; he became President of the Massachusetts Senate; and at length after a well contested election, was sent to take the place of the accomplished Everett in the United States Senate.

His election was a sturdy triumph of principle. His antagonist had every advantage of birth and breeding, every grace which early leisure, constant culture, and the most persevering, conscientious self-education could afford. He was, in graces of person, manners and mind, the ideal of Massachusetts aristocracy, but he wanted that clear insight into actual events, which early poverty and labor had given to his antagonist. His sympathies in the great labor question of the land were with the graceful and cultivated aristocrats rather

[273]

than the clumsy, ungainly laborer; and he but professed the feeling of all aristocrats in saying at the outset of his political life, while Wilson was yet a child, that in the event of a servile insurrection, he would be among the first to shoulder a musket to defend the masters.

But the great day of the Lord was at hand. The events which since have unrolled in fire and blood, had begun their inevitable course; and the plain working-man was taken by the hand of Providence towards the high places where he, with other working men, should shape the destiny of the labor question for this age and for all ages.

Wilson went to Washington in the very heat and fervor of that conflict which the gigantic Giddings, with his great body and unflinching courage, said to a friend, was to him a severer trial of human nerve than the facing of cannon and bullets. The slave aristocracy had come down in great wrath, as if knowing that its time was short. The Senate chamber rang with their oaths and curses as they tore and raged like wild beasts against those whom neither their blandishments nor their threats could subdue. Wilson brought there his face of serene good nature, his vigorous, stocky frame, which had never seen ill-health, and in which the nerves were yet an undiscovered region. It was entirely useless to bully, or to threaten, or to cajole that honest, good-humored, immovable man, who stood like a rock in their way, and took all their fury as unconsciously as a rock takes the foam of breaking waves. In every anti-slavery movement he was always foremost, perfectly awake, perfectly well

[274]

informed, and with that hardy, practical business knowledge of men and things which came from his early education, prepared to work out into actual forms what Sumner gave out as splendid theories.

Wilson’s impression on the Senate was not mainly that of an orator. His speeches were as free from the artifices of rhetoric as those of Lincoln, but they were distinguished for the weight and abundance of the practical information and good sense which they contained. He never spoke on a subject till he had made himself minutely acquainted with it in all its parts, and was accurately familiar with all that belonged to it. Not even John Quincy Adams or Charles Sumner could show a more perfect knowledge of what they were talking about than Henry Wilson. Whatever extraneous stores of knowledge and belles lettres may have been possessed by any of his associates, no man on the floor of the Senate could know more of the United States of America than he; and what was wanting in the graces of the orator, or the refinements of the rhetorician was more than made amends for in the steady, irresistible, strong tread of the honest man, determined to accomplish a worthy purpose.

Wilson succeeded Benton as chairman of the Military Committee of the Senate, and it was fortunate for the country that when the sudden storm of the war broke upon us, so strong a hand held this helm. Gen. Scott said that he did more work in the first three months of the war than had been done in his position before for twenty years; and Secretary Cameron attributed the salvation of Washington in those early days, mainly to Henry Wilson’s power of doing the

[275]

apparently impossible in getting the Northern armies into the field in time to meet the danger.

His recently published account of what Congress has done to destroy slavery, is a history which no man living was better fitted to write. No man could be more minutely acquainted with the facts, more capable of tracing effects to causes, and thus competent to erect this imperishable monument to the honor of his country.

It is meet that the poor, farm-bound apprentice, the shoemaker of Natick, should thus chronicle the great history of the deliverance of labor from disgrace in this democratic nation.

There is something sublime in the history of the movements of the 37th and 38th Congresses of the United States. Perhaps never in any country did an equal number of wise and just men meet together under a more religious sense of their responsibility to God and to mankind. Never had there been a deeper and more religious awe presiding over popular elections than those which sent those men to Congress to man our national ship in the terrors of the most critical passage our stormy world has ever seen. They were the old picked, tried seamen, stout of heart, giants in conscience and moral sense. They were the scarred veterans of long years of battling for the great principles of the Declaration of Independence, men who in old times had come through great battles with the beasts of the slavery Ephesus, and still wore the scars of their teeth. They had seen their president stricken down at their head, and though bleeding inwardly,

[276]

had closed up their ranks shoulder to shoulder, to go steadily on with the great work for which he died.

These men it was who while the din of arms was resounding through the country, while Washington was one great camp and hospital, and the confusing rumors of wars were coming to it from the east and from the west, from the north and from the south—took up and carried to the end the grandest national moral reform ever accomplished in a given time. Many men of the common sort would have said, “This is no time to be driving at moral reforms. We must drive this war through first, and when we have done this, we will begin to wipe up, and adjust, and put away.” So gigantic a war was apology enough to satisfy the consciences of men who looked only to precedents and the rules of ordinary statesmanship, but our Congress was largely made up of men who walked by a higher light, and judged by a higher standard than ever has been given to mere statesmanship before. The spirit of the old Puritans, their unworldly, God-fearing spirit, their steadfast flint-facedness in principle, came to a final and culminating development in these Congresses.

Henry Wilson has written a “History of the Anti-Slavery Measures in Congress,” in a brief, clear, compact summary, and made of it a volume which ought to be in every true American library. It is a volume of which every American has just and honest reason to be proud, and to which every Republican the whole world over, should look with hope and trust, as exhibiting the magnificent morality, the dauntless courage, the unwearied faith, hope and charity that are the

[277]

crown jewels of republics. We should be glad to see this book of Henry Wilson’s in every farm house of New England, lying by the family Bible, under the old flag of the Union. The men who carried through these magnificent reforms—THEY ARE OUR JEWELS.

Mr. Wilson gives in his book a condensed summary of the debates in the House relative to each step of the reform. For the most part it is a record of noble, Christian, unworldly patriotic sentiment—a sort of ideal statesmanship becoming real in tangible good deeds.

Every day some new den in the Augean stable was exposed and opened up to daylight, and the cleansing baptism of liberty applied. There was some fluttering and screaming of owls and bats, and now and then the poor old dilapidated dragon of slavery gave a bootless hiss, but nobody minded it. It was a whole-hearted, clean, pure, noble time in Congress, when those walls, so long defiled with the brawls, the mingled profanity and obscenity of slaveholders and slavebreeders, now rang only to manly sentiments and cleanly, noble, Christian resolves, such as make the heart strong to hear. We quote from the close of Mr. Wilson’s book the summary of what was done by these Congresses in the way of reform legislation.

“As the Union armies advanced into the rebel States, slaves, inspired by the hope of personal freedom, flocked to their encampments, claiming protection against rebel masters, and offering to work and fight for the flag whose stars for the first time gleamed upon their vision with the radiance of liberty. Rebel masters and rebel-sympathizing masters sought the en-

[278]

campments of the loyal forces, demanding the surrender of the escaped fugitives; and they were often delivered up by officers of the armies. To weaken the power of the insurgents, to strengthen the loyal forces, and assert the claims of humanity, the 37th Congress enacted an article of war, dismissing from the service officers guilty of surrendering these fugitives.

Three thousand persons were held as salves in the District of Columbia, over which the nation exercised exclusive jurisdiction; the 37th Congress made these three thousand bondmen freemen, and made slaveholding in the capital of the nation for evermore impossible.

“Laws and ordinances existed in the national capital that pressed with merciless rigor upon the colored persons: the 37th Congress enacted that colored persons should be tried for the same offences, in the same manner, and be subject to the same punishments, as white persons; thus abrogating the ‘black code.’

“Colored persons in the capital of this Christian nation were denied the right to testify in the judicial tribunals; thus placing their property, their liberties, and their lives, in the power of unjust and wicked men; the 37th Congress enacted that persons should not be excluded as witnesses in the courts of the District on account of color.

“In the capital of the nation, colored persons were taxed to support schools from which their own children were excluded; and no public schools were provided for the instruction of more than four thousand youth; the 38th Congress provided by law that public schools should be established for colored children, and that the same rate of appropriations for colored

[279]

schools should be made as are made for schools for the education of white children.

“The railways chartered by Congress, excluded from their cars colored persons, without the authority of law; Congress enacted that there should be no exclusion from any car on account of color.

“Into the territories of the United States,—one third of the surface of the country,—the slaveholding class claimed the right to take and hold their slaves under the protection of law; the 37th Congress prohibited slavery for ever in all the existing territory, and in all territory which may hereafter be acquired; thus stamping freedom for all, for ever, upon the public domain.

“As the war progressed, it became more clearly apparent that the rebels hoped to win the Border slave States; that rebel sympathizers in those States hoped to join the rebel States; and that emancipation in loyal States would bring repose to them, and weaken the power of the Rebellion; the 37th Congress, on the recommendation of the President, by the passage of a joint resolution, pledged the faith of the nation to aid loyal States to emancipate the slaves therein.

“The hoe and spade of the rebel slave were hardly less potent for the Rebellion than the rifle and bayonet of the rebel soldier. Slaves sowed and reaped for the rebels, enabling the rebel leaders to fill the wasting ranks of their armies, and feed them. To weaken the military forces and the power of the Rebellion, the 37th Congress decreed that all slaves of persons giving aid and comfort to the Rebellion, escaping from such persons, and taking refuge within

[280]

the lines of the army; all slaves captured from such persons, or deserted by them; all slaves of such persons, being within any place occupied by rebel forces, and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States,—shall be captives of war, and shall be for ever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.

“The provisions of the Fugitive-slave Act permitted disloyal masters to claim, and they did claim, the return of their fugitive bondmen; the 37th Congress enacted that no fugitive should be surrendered until the claimant made oath that he had not given aid and comfort to the Rebellion.

“The progress of the Rebellion demonstrated its power, and the needs of the imperiled nation. To strengthen the physical forces of the United States, the 37th Congress authorized the President to receive into the military service persons of African descent; and every such person mustered into the service, his mother, his wife and children, owing service or labor to any person who should give aid and comfort to the Rebellion, was made for ever free.

“The African slave-trade had been carried on by slave pirates under the protection of the flag of the United States. To extirpate from the seas that inhuman traffic, and to vindicate the sullied honor of the nation, the Administration early entered into treaty stipulations with the British Government for the mutual right of search within certain limits; and the 37th Congress hastened to enact the appropriate legislation to carry the treaty into effect.

“The slaveholding class, in the pride of power, persistently refused to recognize the independence of

[281]

Hayti and Liberia; thus dealing unjustly towards those nations, to the detriment of the commercial interests of the country; the 37th Congress recognized the independence of those republics by authorizing the President to establish diplomatic relations with them.

“By the provisions of law, white male citizens alone were enrolled in the militia. In the amendment to the acts for calling out the militia, the 37th Congress provided for the enrollment and drafting of citizens, without regard to color; and, by the Enrollment Act, colored persons, free or slave, are enrolled and drafted the same as white men. The 38th Congress enacted that colored soldiers shall have the same pay, clothing, and rations, and be placed in all respects upon the same footing, as white soldiers. To encourage enlistments, and to add emancipation, the 38th Congress decreed that every slave mustered into the military service shall be free for ever; thus enabling every slave fit for military service to secure personal freedom.

“By the provisions of the fugitive-slave acts, slave-masters could hunt their absconding bondmen, require the people to aid in their recapture, and have them returned at the expense of the nation. The 38th Congress erased all fugitive-slave acts from the statutes of the Republic.

“The law of 1807 legalized the coastwise slave-trade; the 38th Congress repealed that act, and made the trade illegal.

“The courts of the United States receive such testimony as is permitted in the States where the courts are holden. Several of the States exclude the testi-

[282]

mony of colored persons. The 38th Congress made it legal for colored persons to testify in all the courts of the United States.

“Different views are entertained by public men relative to the reconstruction of the governments of the seceded States, and the validity of the President’s proclamation of emancipation. The 38th Congress passed a bill providing for the reconstruction of the governments of the rebel States, and for the emancipation of the slaves in those States; but it did not receive the approval of the President.

“Colored persons were not permitted to carry the United States mails; the 38th Congress repealed the prohibitory legislation, and made it lawful for persons of color to carry the mails.

“Wives and children of colored persons in the military and naval service of the United States were often held as slaves; and, while husbands and fathers were absent fighting the battles of the country, these wives and children were sometimes removed and sold, and often treated with cruelty; the 38th Congress made free the wives and children of all persons engaged in the military or naval service of the country.

“The disorganization of the slave system, and the exigencies of civil war, have thrown thousands of freedmen upon the charity of the nation; to relieve their immediate needs, and to aid them through the transition period, the 38th Congress established a Bureau of Freedmen.

“The prohibition of slavery in the Territories, its abolition in the District of Columbia, the freedom of colored soldiers, their wives and children, emancipation

[283]

in Maryland, West Virginia, and Missouri, and by the re-organized State authorities of Virginia, Tennessee, and Louisiana, and the President’s Emancipation Proclamation, disorganized the slave system, and practically left few persons in bondage; but slavery still continued in Delaware and Kentucky, and the slave codes remain, unrepealed in the rebel States. To annihilate the slave system, its codes and usages; to make slavery impossible, and freedom universal,—the 38th Congress submitted to the people an anti-slavery amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The adoption of that crowning measure assures freedom to all.

“Such are the “ANTI-SLAVERY MEASURES” of the Thirty-seventh and Thirty-eighth Congresses during the past four crowded years. Seldom in the history of nations is it given to any body of legislators or law-givers to enact or institute a series of measures so vast in their scope, so comprehensive in their character, so patriotic, just, and humane.

“But, while the 37th and 38th Congresses were enacting this anti-slavery legislation, other agencies were working to the consummation of the same end,—the complete and final abolition of slavery. The President proclaims three and a half millions of bondmen in the rebel States henceforward and for ever free. Maryland, Virginia, and Missouri adopt immediate and unconditional emancipation. The partially re-organized rebel States of Virginia and Tennessee, Arkansas and Louisiana, accept and adopt the unrestricted abolition of slavery. Illinois and other States hasten to blot from their statute-books their dishonoring black codes.

[284]

The Attorney-General officially pronounces the negro a citizen of the United States. The negro, who had no status in the Supreme Court, is admitted by the Chief Justice to practice as an attorney before that august tribunal. Christian men and women follow the loyal armies with the agencies of mental and moral instruction to fit and prepare the enfranchised freedmen for the duties of the higher condition of life now opening before them.”

We cannot quit this subject without remarking on the striking character of the debates Mr. Wilson’s book records on these subjects. The great majority of Congress utters aloud and with the consent, just, manly, noble, humane, large-hearted sentiments and resolves, while a poor wailing minority is picking up and retailing the old worn out jokes and sneers and incivilities and obscenities of the dying dragon of slavery.

As a specimen of the utter naivete and ignorance of comity and good manners induced by slavery, in contrast with the courtesy and refinement of true republicanism, we give this fragment of a debate on the recognition of Hayti and Liberia.

Mr. Davis, of Kentucky, after plaintively stating that he is weary, sick, disgusted, despondent with the introduction of slaves and slavery into this chamber, proceeds to state his terror lest should these measures take effect, these black representatives would have to be received on terms of equality with those of other nations. Mr. Davis goes on to say: “A big negro fellow, dressed out in his silver and gold lace, presented himself in the court of Louis Napoleon, I admit, and was received. Now, sir, I want no such exhibition as

[285]

that in our country. The American minister, Mr. Mason, was present on that occasion; and he was sleeved by some Englishman—I have forgotten his name—who was present, who pointed out to him the ambassador of Soulouque, and said, ‘What do you think of him?’ Mr. Mason turned round and said, ‘I think, clothes and all, he is worth a thousand dollars.’”

Mr. Davis evidently considered this witticism of Mr. Mason’s as both a specimen of high bred taste and a settling argument.

In reply, Mr. Sumner drily says: “The Senator alludes to some possible difficulties, I hardly know how to characterize them, which may occur here in social life, should the Congress of these United States undertake at this late day, simply in harmony with the law of nations, and following the policy of civilized communities, to pass the bill under discussion. I shall not follow the senator on those sensitive topics. I content myself with a single remark. I have more than once had the opportunity of meeting citizens of these republics; and I say nothing more than truth when I add, that I have found them so refined, and so full of self-respect, that I am led to believe no one of them charged with a mission from his government, will seek any society where he will not be entirely welcome. Sir, the senator from Kentucky may banish all anxiety on that account. No representative from Hayti or Liberia will trouble him.”

Mr. Crittenden of Kentucky said: “I will only say, sir, that I have an innate sort of confidence and pride that the race to which we belong is a superior race among the races of the earth, and I want to see that

[286]

pride maintained. The Romans thought that no people on the face of the earth were equal to the citizens of Rome, and it made them the greatest people in the world. * * * The spectacle of such a diplomatic dignitary in our country, would, I apprehend, be offensive to the people for many reasons, and wound their habitual sense of superiority to the African race.”

Mr. Thomas of Maine, on the other hand, presents the true basis of Christian chivalry: “I have no desire to enter into the question of the relative capacity of races; but if the inferiority of the African race were established, the inference as to our duty would be very plain. If this colony has been built up by an inferior race of men, they have upon us a yet stronger claim for our countenance, recognition, and, if need be, protection. The instincts of the human mind and heart concur with the policy of men and governments to help and protect the weak. I understand that to a child or to a woman I am to show a degree of forbearance, kindness, and of gentleness even, which I am not necessarily to extend to my equal.”

In like manner contrast a passage of sentiment between two senators on the education bill.

Mr. Carlile of Virginia, “did not see any good reason why the Congress of the United States should itself enter upon a scheme for educating negroes.” He understood “the reason assigned for the government of a State undertaking the education of the citizens of the State is that the citizens in this country are the governors;” but he presumed “we have not yet reached the point when it is proposed to elevate to the condition of voters the negroes of the land.”

[287]

Mr. Grimes in reply said, “It may be true, that, in that section of the country where the senator is most acquainted, the whole idea of education proceeds from the fact, that the person who is to be educated is merely to be educated because he is to exercise the elective franchise; but I thank God that I was raised in a section of the country where there are nobler and loftier sentiments entertained in regard to education. We entertain the opinion that all human beings are accountable beings. We believe that every man should be taught so that he may be able to read the law by which he is to be governed, and under which he may be punished. We believe that every accountable being should be able to read the word of God, by which he should guide his steps in this life, and shall be judged in the life to come. We believe that education is necessary in order to elevate the human race. We believe that it is necessary in order to keep our jails and our penitentiaries and our alms-houses free from inmates. In my section of the country, we do not educate any race upon any such low and groveling ideas as those that seem to be entertained by the senator from Virginia.”

But the warmest battle was on the question of the right of colored persons to ride in the cars. The chivalry maintained their side by such kind of language as this: “Has any gentleman who was born a gentleman, or any man who has the instincts of a gentleman, felt himself degraded by the fact that he was not honored by a seat beside some free negro? Has any lady in the United States felt herself aggrieved

[288]

that she was not honored with the company of Miss Dinah or Miss Chloe, on board these cars?”

Again, in

the course of the debate, another senator says of Mr. Sumner, “He

may ride with negroes, if he thinks proper, so may I; but if I see proper not

to do so, I shall follow my natural instincts, as he follows his.”

“I shall vote for this amendment,”

says Henry Wilson; “and my own observation convinces me that justice, not to

say decency, requires that I should do so.

Some weeks ago, I rode to the capitol in one of these cars. On the front part of the car, standing with

the driver, were, I think, five colored clergymen of the Methodist Episcopal

church, dressed like gentlemen, and behaving like gentlemen. These clergymen were riding with the driver

on the front platform, and inside the car were drunken loafers, conducting and

behaving themselves so badly that the conductor threatened to turn them out.”

“The senator from Illinois tells

us,” said Mr. Wilson, “that the colored people have a legal right to ride in these

cars now. We know it; nobody doubts it;

but this company into which we breathed the breath of life, outrages the rights

of twenty-five thousand colored people in this District, in our presence, in

defiance of our opinions. * *

* I tell the senator from

Illinois that I care far more for the rights of the humblest black child that

treads the soil of the District of Columbia than I do for the prejudices of

this corporation, and its friends and patrons.

The rights of the humblest colored man in the capital of this Christian

nation are dearer to me than the commendations

[289]

or the thanks of

all persons in the city of Washington who sanction this violation of the rights

of a race. I give this vote, not to

offend this corporation, not to offend anybody in the District of Columbia, but

to protect the rights of the poor and the lowly, trodden under the heel of

power. I trust we shall protect rights,

if we do it over prejudices and over interests, until every man in this country

is fully protected in all the rights that belong to beings made in the image of

God. Let the free man of this race be

permitted to run the career of life; to make of himself all that God intended

he should make, when he breathed into him the breath of life.”

So there they had it, at the mouth

of an educated northern working-man, who knew what man as man was worth, and

the retiring senators, giving up the battle, wailed forth as follows:

“Poor, helpless, despised, inferior

race of white men, you have very little interest in this government, you are

not worth

consideration in

the legislation of this country; but let your superior Sambo’s interest come in

question, and you will find the most tender interest on his behalf. What a pity there is

not somebody to lamp-black white men, so that their rights could be secured.”

Mr. Powell thought that the Senator

from Massachusetts, the next time one of his Ethiopian friends comes to

complain to him on the subject, should bring an action for him in court, and

adds, with the usual good taste of his party:

* * “The Senator has indicated to his fanatical brethren those people

who meet in free love societies, the old ladies and the sensa-

[290]

tion preachers, and

those who live on fanaticism, that he has offered it, and I see no reason why

we should take up the time of the Senate in squabbling over the Senator’s

amendments, introducing the negro into every wood-pile that comes along.”

Mr. Saulsbury closes a discussion on

negro testimony with the following pious ejaculation: “He did not wish to say any more about the nigger aspect of the case. It is here

every day; and I suppose it will be here every day for years to come, till

the Democratic party comes in power and wipes all legislation of this character

out of the statute-book, which I trust in God they will do.”

All this sort of talk, shaken in the

face of the joyous band of brothers who were going on their way rejoicing,

reminds us forcibly of John Bunyan’s description of the poor old toothless

giant, who in his palmy days used to lunch upon pilgrims, tearing their flesh

and cracking their bones in the most comfortable way possible, but who now

having sustained many a severe brush, was so crippled with rheumatism that he

could only sit in the mouth of his cave, mumbling, “You will never mend till

more of you are burned.”

Thank God for the day we live in,

and for such men as Henry Wilson and his compeers of the 37th and 38th

Congresses. They have at last put our

American Union in that condition which old Solon gave as his ideal of true

Democracy, namely:

A STATE WHERE AN

INJURY TO THE MEANEST MEMBER IS FELT AS AN INJURY TO THE WHOLE.

[293]

CHAPTER VII.

HORACE GREELEY.

The Scotch-Irish

Race in the United States—Mr. Greeley a Partly Reversed Specimen of it—His

Birth and Boyhood—Learns to Read Books Upside Down—His Apprenticeship on a

Newspaper—The Town Encyclopaedia—His Industry at his Trade—His First Experience

of a Fugitive Slave Chase—His First Appearance in New York—The Work on the

Polyglot Testament—Mr. Greeley as “the Ghost”—The First Cheap Daily Paper—The

firm of Greeley & Story—The New Yorker, the Jeffersonian and the Log

Cabin—Mr. Greeley as Editor of the New Yorker—Beginning of The Tribune—Mr.

Greeley’s Theory of a Political Newspaper—His Love for The Tribune—The First

Week of that Paper—The Attack of the Sun and its Result—Mr. McElrath’s

Partnership—Mr. Greeley’s Fourierism—“The Bloody Sixth”—The Cooper Libel

Suits—Mr. Greeley in Congress—He goes to Europe—His course in the Rebellion—His

Ambition and Qualifications for Office—The Key-Note of his Character.

No race has stronger

characteristics, bodily or mental, than that powerful, obstinate, fiery, pious,

humorous, honest, industrious, hard-headed, intelligent, thoughtful and

reasoning people, the Scotch-Irish. The

vigorous qualities of the Scotch-Irish have left broad and deep traces upon the

history of the United States. As if

with some hereditary instinct, they settled along the Allegheny ridge,

principally from Pennsylvania to Georgia, in the fertile valleys and broader

expanses of level land on either side, especially to the westward. In the healthy and genial air of these

regions, renowned for the handsomest breed of men and women in the world, the

Scotch-Irish acted out with thorough freedom, all the vigorous and often

violent impulses of their nature. They

were pioneers, Indian-fighters, politicians, theologians;

[294]

and they were as

polemic in everything else as in theology.

Jackson and Calhoun were of this blood.

An observant traveler in Tennessee described to the writer the interest

with which he found in that state literally hundreds of forms and faces with

traits so like the lean erect figure, high narrow head, stiff black hair, and

stern features of the fighting old President, that they might have been his

brothers. Many of our eminent

Presbyterian theologians like the late Dr. Wilson, of Cincinnati, have been

Scotch-Irish too, and with their spiritual weapons they have waged many a

controversy as unyielding, as stern and as unsparing as the battle in which

Jackson beat down Calhoun by showing him a halter, or as that brutal knife

fight in which he and Thomas H. Benton nearly cut each other’s lives out.

Horace Greeley is of this

Scotch-Irish race, and after a rule which physiologists well know to be not

very uncommon, he presents a direct reverse of many of its traits, more

especially its physical ones. Instead

of a lean, erect person, dry hard muscles, a high narrow head, coarse stiff

black hair, and a stern look, he tends to be fat, is shambling and bowed over

in carrying himself, thinskinned and smooth and fair as a baby; with a wide,

long, yet rounded head, silky-fine almost white hair, and a habitually meek

sort of smile, which however must not be trusted to as an index of the mind within. Meek as he looks, no man living is readier

with a strong sharp answer.

Non-resistant as he is physically, there is not a more uncompromising an

opponent and intense combatant in these United States. Mentally, he shows a predominance of Scotch-

[295]

Irish blood

modified by certain traits which reveal themselves in his readiness to receive

new theories of life.

Mr. Greeley was born Feb. 3d, 1811,

at his father’s farm, in Amherst, New Hampshire. The town was part of a district first settled by a small company

of sixteen families of Scotch-Irish from Londonderry. These were part of a considerable emigration in 1718 from that

city, whose members at first endeavored to settle in Massachusetts; but they

were so ill received by the Massachusetts settlers that they found it necessary

to scatter away into distant parts of the country before they could find rest

for the soles of their feet.

The ancestors of Mr. Greeley were

farmers, those of the name of Greeley being often also blacksmiths. The boy was fully occupied with hard farm

work, and he attended the American farmers’ college, the District School. He had an intense natural love for acquiring

knowledge, and learned to read of himself.

He could read any child’s book when he was three, and any ordinary book

at four; and having, as his biographer, Mr. Parton, suggests, still an overplus

of mental activity, he learned to read as readily with the book side ways or

upside down, as right side up.

Mr. Greeley, like a number of men

who have grown up to become capable of a vast quantity of hard work and

usefulness, was extremely feeble at birth, and was even thought scarcely likely

to live when he first entered the world.

During his first year he was feeble and sickly. His mother, who had lost her two children

born next before him, seemed to be doubly fond of her weak little one, both for

the sake of those that

[296]

were gone, and of

his very weakness, and she kept him by her side much more closely than if he

had been strong and well; and day after day, she sung and repeated to him an

endless store of songs and ballads, stories and traditions. This vivid oral literature doubtless had

great influence in stimulating the child’s natural aptitude for mental

activity.

Mr. Greeley’s father was not a much

better financier than his son. In 1820,

in spite of all the honest hard-work that he could do, he became bankrupt, and

in 1821 moved to a new residence in Vermont.

Mr. Greeley seems to have had such

an inborn instinct after newspapers and newspaper work, as Mozart had for music

and musical composition. He himself

says on this point, in his own “Recollections” in The New York Ledger, “Having

loved and devoured newspapers—indeed every form of periodical—from childhood, I

early resolved to be a printer if I could.”

When only eleven years old he applied to be received as an apprentice in

a newspaper office at Whitehall, Vt., and was greatly cast down by being

refused for his youth. Four years

afterwards, in the spring of 1826, he obtained employment in the office of the

Northern Spectator, at East Poultney, Vt., and thus began his professional

career.

As a young man, Mr. Greeley was not

only poorly but most extremely carelessly dressed; absent minded yet observant;

awkward and indeed clownish in his manners; extremely fond of the game of

checkers, at which he seldom found an equal; and of fishing and

bee-hunting. Fonder still he was of

reading and acquiring general knowledge, for which a public library

[297]

in the town offered

valuable advantages; and he very soon became, as a biographer says, a “town

encyclopedia,” appealed to as a court of last resort, by every one who was at a

loss for information. In the local

debating society of the place he was assiduous and prominent, and was

noticeable both for the remarkable body of detailed facts which he could bring

to bear upon the questions discussed, and for his thorough devotion to his

argument. Whatever his opinion was, he

stuck to it against either reasoning or authority.

In his calling as a printer, he was

most laborious, and quickly became the most valuable hand in the office. He also began here his experience as a

writer—if that may be called written which was never set down with a pen. For he used to compose condensations of news

paragraphs, and even original paragraphs of his own, framing his sentences in

his mind as he stood at the case, and setting them up in type entirely without

the intermediate process of setting them down in manuscript. This practice was exactly the way to

cultivate economy, clearness, and directness of style; as it was necessary to

know accurately what was to be said, or else the letters in the composing stick

would have to be distributed and set up again; and it was natural to use the

fewest and plainest possible words.

While Horace was thus at work, his

father had again removed beyond the Alleghanies, where he was doing his best to

bring some new land under cultivation.

The son, meanwhile, and for some time after his apprenticeship too, used

to send his father all the money that he could save from his scanty wages. He con-

[298]

tinued to assist

his father, indeed, until the latter was made permanently comfortable upon a

valuable and well stocked farm; and even paid up some of his father’s old debts

in New Hampshire thirty years after they were contracted.

Mr. Greeley has recorded that while

in Poultney he witnessed a fugitive slave chase. New York had then yet a remainder of slavery in her, in the

persons of a few colored people who had been under age when the state abolished

slavery, and had been left by law to wait for their freedom until they should

be twenty-eight years old. Mr. Greeley

tells the story in the N. Y. Ledger, in sarcastic and graphic words, as

follows:

“A young negro who must have been

uninstructed in the sacredness of constitutional guaranties, the rights of

property, &c., &c., &c., feloniously abstracted himself from his

master in a neighboring New York town, and conveyed the chattel personal to our

village; where he was at work when said master, with due process and following,

came over to reclaim and recover the goods.

I never saw so large a number of men and boys so suddenly on our

village-green, as his advent incited; and the result was a speedy disappearance

of the chattel, and the return of his master, disconsolate and niggerless, to

the place whence he came. Everything on

our side was impromptu and instinctive, and nobody suggested that envy or hate

of the South, or of New York, or of the master, had impelled the rescue. Our people hated injustice and oppression,

and acted as if they couldn’t help it.”

In June 1830, the Northern Spectator

was discontinued, and our encyclopedic apprentice was turned

[299]

loose on the

world. Hereupon he traveled, partly on

foot and partly by canal, to his father’s place in Western Pennsylvania. Here he remained a while, and then after one

or two unsuccessful attempts to find work, succeeded at Erie, Pa., where he was

employed for seven months. During this

time his board with his employer having been part of his pay, he used for other

personal expenses six dollars in cash.

The wages remaining due him amounted to just ninety-nine dollars. Of this he now gave his father eighty-five, put

the rest in his pocket and went to New York.

He reached the city on Friday morning

at sunrise, August 18th, 1831, with ten dollars, his bundle, and his

trade. He engaged board and lodging at

$2.50 a week, and hunted the printing offices for employment during that day

and Saturday in vain; fell in with a fellow Vermonter early Monday morning, a

journeyman printer like himself, and was by him presented to his foreman. Now there was in the office a very difficult

piece of composition, a polyglot testament, on which various printers had refused

to work. The applicant was, as he always

had been, and will be, very queer looking; insomuch that while waiting for the

foreman’s arrival, the other printers had been impelled to make many personal

remarks about him. But though equally

entertained with his appearance, the foreman, rather to oblige the introducer

than from any admiration of the new hand, permitted him a trial, and he was set

at work on the terrible Polyglot. We

transcribe Mr. Parton’s lively account of the sequel:

“After Horace had been at work an

hour or two, Mr. West, the ‘boss,’ came into the office. What his

[300]

feelings were when

he saw the new man may be inferred from a little conversation on the subject

which took place between him and the foreman:

“’Did you hire that d----- fool?’

asked West, with no small irritation.

“’Yes; we must have hands, and he’s

the best I could get,’ said the foreman, justifying his conduct, though he was

really ashamed of it.

“’Well,’ said the master, ‘for

Heaven’s sake pay him off to-night, and let him go about his business.’

“Horace worked through the day with

his usual intensity, and in perfect silence.

At night he presented to the foreman, as the custom then was, the

‘proof’ of his day’s work. What astonishment

was depicted in the good-looking countenance of that gentleman, when he

discovered that the proof before him was greater in quantity and more correct

than that of any other day’s work on the Polyglot! There was no thought of sending the new journeyman about his

business now. He was an established man

at once. Thenceforward, for several

months, Horace worked regularly and hard on the Testament, earning about six

dollars a week.”

While a journeyman here, he worked

very hard indeed, as he was paid by the piece, and the work was necessarily

slow. At the same time, according to

his habit, he was accustomed to talk very fluently, his first day’s silent

labor having been an exception; and his voluble and earnest utterance,

singular, high voice, fullness, accuracy, and readiness with facts, and

positive though good-natured tenacious disputatiousness, together with his very

marked personal traits, made him

[301]

the phenomenon of

the office. His complexion was so fair,

and his hair so flaxen white, that the men nicknamed him “the Ghost.” The mischievous juniors played him many

tricks, some of them rough enough, but he only begged to be let alone, so that

he might work, and they soon got tired of teasing from which there was no

reaction. Besides, he was forever

lending them money, for like very many of the profession, the other men in the

office were profuse with whatever funds were in hand, and often needy before

pay-day; while his own unconscious parsimony in personal expenditures was to

him a sort of Fortunatus’ purse—an unfailing fountain.

For about a year and a half Mr. Greeley

worked as a journeyman printer. During

1832 he had become acquainted with a Mr. Story, an enterprising young printer,

and also with Horatio D. Sheppard, the originator of the idea of a Cheap Daily

Paper. The three consulted and

co-operated; in December the printing firm of Greeley & Story was formed,

and on the first of January, 1833, the first number of the cheap New York

Daily, “The Morning Post,” was issued, “price two cents,” Dr. Sheppard being

editor. Various disadvantages stopped

the paper before the end of the third week, but the idea was a correct

one. The New York Sun, issued in

accordance with it nine months later, is still a prosperous newspaper; and the

great morning dallies of New York, including the Tribune, are radically upon

the same model.

Though this paper stopped, the job

printing firm of Greeley & Story went on and made money. At

[302]

Mr. Story’s death,

July 9, 1833, his brother-in-law, Mr. Winchester, took his place in the

office. In 1834 the firm resolved to

establish a weekly; and on March 22d, 1834, appeared the first number of the

Weekly New Yorker, owned by the firm, and with Mr. Greeley as editor. He had now found his proper work, and he has

pursued it ever since with remarkable force, industry and success.

This success, however, was only

editorial, not financial, so far as the New Yorker was concerned. The paper began with twelve subscribers, and

without any flourishes or promises. By

its own literary, political and statistical value, its circulation rose in a year

to 4,500, and afterwards to 9,000. But

when it stopped, Sept. 20, 1841, it left its editor laboring under troublesome

debts, both receivable and payable. The

difficulty was manifold; its chief sources were, Mr. Greeley’s own deficiencies

as a financier, supplying too many subscribers on credit, and the great

business crash of 1837.

During the existence of the New

Yorker, Mr. Greeley also edited two short-lived but influential campaign

political sheets. One of these, the

Jeffersonian, was published weekly, at Albany.

This was a Whig paper, which appeared during a year from March, 1838,

and kept its editor over-busy, with the necessary weekly journey to Albany, and

the double work. The other was the Log

Cabin, the well-known Harrison campaign paper, issued weekly during the

exciting days of “Tippecanoe and Tyler too,” in 1840, and which was continued

as a family paper for a year afterwards.

Of the very first number of this famous little sheet,

[303]

48,000 were sold,

and the edition rapidly increased to nearly 90,000. Neither of these two papers, however, made much money for their

editor. But during his labors on the

three, the New Yorker, Jeffersonian, and Log Cabin, he had gained a standing as

a political and statistical editor of force, information and ability.

Mr. Greeley’s editorial work on the

New Yorker was a sort of literary spring-time to him. The paper itself was much more largely literary than the Tribune

now is. In his editorial writing in

those days, moreover, there is a certain rhetorical plentifulness of expression

which the seriousness and the pressures of an overcrowded life have long ago

cut sharply and closely off; and he even frequently indulged in poetical

compositions. This ornamental material,

however, was certainly not his happiest kind of effort. Mr. Greeley does his best only by being

wholly utilitarian. Poetry and rhetoric

appear as well from his mind as a great long red feather would, sticking out of

his very oldest white hat.

The great work of Mr. Greeley’s

life, however—The New York Tribune—had not begun yet, though he was thirty

years old. Its commencement was

announced in one of the last numbers of the Log Cabin, for April 10, 1841, and

its first number appeared on the very day of the funeral solemnities with which

New York honored the memory of President Harrison. Mr. Greeley’s own account, in one of his articles in the New York

Ledger, is an interesting statement of his Theory of a Political Newspaper. He says:

“My leading idea was the

establishment of a journal removed alike from servile partizanship on the one

[304]

hand, and from

gagged, mincing neutrality on the other.

Party spirit is so fierce and intolerant in this country, that the

editor of a non-partizan sheet is restrained from saying what he thinks and

feels on the most vital, imminent topics; while, on the other hand, a

Democratic, Whig, or Republican journal is generally expected to praise or

blame, like or dislike, eulogize or condemn, in precise accordance with the

views and interest of its party. I

believed there was a happy medium between these extremes—a position from which

a journalist might openly and heartily advocate the principles and commend the

measures of that party to which his convictions allied him, yet dissent frankly

from its course on a particular question, and even denounce its candidates if

they were shown to be deficient in capacity, or (far worse) in integrity. I felt that a journal thus loyal to its own

convictions, yet ready to expose and condemn unworthy conduct or incidental

error on the part of men attached to its party, must be far more effective,

even party-wise, than though it might always be counted on to applaud or

reprobate, bless or curse, as the party prejudices or immediate interest might

seem to prescribe.”

Mr. Greeley has now been the chief

editor of the Tribune for twenty-six years, and the persistent love with which

he still regards his gigantic child strikingly appears in the final paragraph

of the same article:

“Fame is a vapor; popularity and

accident; riches take wings; the only earthly certainty is oblivion—no man can

foresee what a day may bring forth; and those who cheer to-day will often curse

to-morrow; and yet

[305]

I cherish the hope

that the Journal I projected and established will live and flourish long after

I shall have moldered into forgotten dust, being guided by a larger wisdom, a

more unerring sagacity to discover the right, though not by a more unfaltering

readiness to embrace and defend it at whatever personal cost; and that the stone

which covers my ashes may bear to future eyes the still intelligible

inscription, ‘Founder of THE NEW YORK

TRIBUNE. ”

The Tribune began with some 600

subscribers. Of its first number 5,000

copies were printed, and, as Mr. Greeley himself once said, he “found some

difficulty in giving them away.” At the

end of the first week the cash account stood, receipts, $92; expenditures,

$525. Now the proprietor’s whole money

capital was $1,000, borrowed money.

But—as has more than once been the case with others—an unjust attack on

the Tribune strengthened it. An

unprincipled attempt was made by the publisher of the Sun, to bribe and bully

the newsmen and then to flog the newsboys out of selling the Tribune. The Tribune was prompt in telling the story

to the public, and the public showed that sense of justice so natural to all

communities, by subscribing to it at the rate of three hundred a day for three

weeks at a time. In four weeks it sold

an edition of six thousand, and in seven it sold eleven thousand, which was

then all that it could print. Its

advertising patronage grew equally fast.

And what was infinitely more than this rush of subscribers, a steady and

judicious business man became a partner with Mr. Greeley in the paper, at the

end of July, not four months from its first issue. This was Mr.

[306]

Thomas McElrath,

whose sound business management undoubtedly supplied to the concern an element

more indispensable to its continued prosperity, than any editorial ability

whatever.

The Tribune, as we have seen, like

the infant Hercules in the old fable, successfully resisted an attempt to

strangle it in its cradle. From that

time to this, the paper and its editor have lived in a healthy and invigorating

atmosphere of violent attacks of all sorts, on grounds political, social, moral

and religious. The paper has not been

found fault with, however, for being flat or feeble or empty. The first noticeable disturbance after the

Sun attack was the Fourierite controversy.

Perhaps Mr. Greeley’s Fourierism—or Socialism, as it might be better

called—was the principal if not the sole basis of all the notorious uproars

that have been made for a quarter of a century about his “isms,” and his being

a “philosopher.” During 1841 and

several following years, the Tribune was the principal organ in the United

States of the efforts then made to exemplify and prove in actual life the

doctrines of Charles Fourier. The paper

was violently assaulted with the charge that these doctrines necessarily

implied immorality and irreligion. The

Tribune never was particularly “orthodox,” and while it vigorously defended

itself, it could not honestly in doing so say what would satisfy the stricter

doctrinalists of the different orthodox religious denominations. Moreover, the practical experiments made to

organize Fourierite “phalanxes” and the like, all failed; so that in one sense,

both the Fourierite movement was a failure, and The Tribune was vanquished in

the discussion.

[307]

But the controversy

was a great benefit to the cause of associated human effort; and there can be

no doubt that the various endeavors at the present day in progress to apply the

principle of association to the easing and improving of the various concerns of

life, present a much more hopeful prospect than would have been the case

without the ardent and energetic advocacy of The Tribune.

The next quarrel was with “the

Bloody Sixth,” as it was called, i. e. the low and rowdy politicians of the

Sixth Ward, then the most corrupt part of the city. These politicians and their followers, enraged at certain

exposures of their misdeeds in the spring of 1842, demanded a retraction, and

only getting a hotter denunciation than before, promised to come down and

“smash the office.” The whole

establishment was promptly armed with muskets; arrangements were made for

flinging bricks from the roof above and spurting steam from the engine boiler

below; but the “Bloody Sixth” never came.

The Cooper libel suits were in

consequence of alleged libelous matter about J. Fenimore Cooper, who was a

bitter tempered and quarrelsome man, and to the full as pertinacious as Mr.

Greeley himself. This matter was

printed November 17, 1841. The first

suit in consequence was tried December 9, 1842. The damages were laid at $3,000.

Cooper and Greeley each argued on his own side to the Court, and Cooper

got a verdict for $200. Mr. Greeley

went home and wrote a long and sharp narrative of the whole, for which Cooper

instantly brought another suit; but he found

[308]

that his prospect

this time did not justify his perseverance, and the suit never came to trial.

In 1844 Mr. Greeley worked with

tremendous intensity for the election of Henry Clay, but to no purpose. In February, 1845, the Tribune office was

thoroughly burnt out, but fortunately with no serious loss. The paper was throughout completely opposed

to the Mexican War. In 1848, and

subsequently, the paper at first with hopeful enthusiasm and at last with sorrow

chronicled the outbreak, progress and fate of the great Republican uprising in

Europe. During the same year Mr.

Greeley served a three months’ term in Congress, signalizing himself by a

persistent series of attacks both in the House and in his paper, on the

existing practice in computing and paying mileage—a comparatively petty swindle,

mean enough doubtless, in itself, but very far from being the national evil

most prominently requiring a remedy.

This proceeding made Mr. Greeley a number of enemies, gained him some

inefficient approbations, and did not cure the evil. In 1857 he went to Europe, to see the “Crystal Palace” or World’s

Fair at London, in that year. He was a

member of one of the “juries” which distributed premiums on that occasion;

investigated industrial life in England with some care; and gave some

significant and influential information about newspaper matters, in testifying

before a parliamentary committee on the repeal of certain oppressive taxes on

newspapers. He made a short trip to

France and Italy; and on his return home, reaching the dock at New York about 6

A. M., he had already made up the matter for an “extra,” while on board the

steamer.

[309]

He rushed at once

to the office, seizing the opportunity to “beat” the other morning papers, by

an “exclusive” extra, sent off for the compositors, who had all gone to bed at

their homes; began setting up the matter himself; worked away along with the

rest until his exclusive extra was all ready, and then departed contentedly to

his own home.

Mr. Greeley had always been a

natural abolitionist; but, with most of the Whig party, he had been willing to

allow the question of slavery to remain in a secondary position for a long

time. He was however a willing, early,

vigorous and useful member of the Republican party, when that party became an

unavoidable national necessity, as the exponent of Freedom. With that party he labored hard during the

Fremont campaign, through the times of the Kansas wars, and for the election of

Mr. Lincoln. When the Rebellion broke

out he stood by the nation to the best of his ability, and if he gave mistaken

counsels at any time, his mistakes were the unavoidable results of his mental

organization, and not in the least due to any conscious swerving from

principle, either in ethics or in politics.

Mr. Greeley has at various times

been spoken of as a candidate for State offices, and he undoubtedly has a

certain share of ambition for high political position—an ambition which is

assuredly entitled to be excused if not respected by American citizens. Yet any sound mind, it is believed, must be

forced to the belief that his highest and fittest place is the Chief Editor’s

chair in the office of The Tribune.

There he wields a great, a laboriously and honestly acquired influence,

an in-

[310]

fluence of the

greatest importance to Society. His friends

would be sorry to see him leave that station for any other.

Mr. Greeley’s character and career

as an editor and politician can be understood and appreciated by remembering

his key note:—Benevolent ends, by

utilitarian means.

He desires the amelioration of all

human conditions and the instrumentalities which he would propose are generally

practical, common sense ones. Of

magnificence, of formalities, of all the conventional part of life, whether in

public or private, he is by nature as utterly neglectful as he is of the dandy

element in costume, but he has a solid and real appreciation of many

appreciable things, which go to make up the sum total of human advancement and

happiness.

[311]

CHAPTER VIII.

DAVID GLASCOE FARRAGUT.

The Lesson of the

Rebellion to Monarchs—The Strength of the United States—The U. S. Naval

Service—The Last War—State of the Navy in 1861—Admiral Farragut Represents the

Old Navy and the New—Charlemagne’s Physician, Farraguth—The Admiral’s Letter

about his Family—His Birth—His Cruise with Porter when a Boy of Nine—The

Destruction of the Essex—Farragut in Peace Times—Expected to go with the

South—Refuses, is Threatened, and goes North—The Opening of the Mississippi—The

Bay Fight at Mobile—The Admiral’s Health—Farragut and the Tobacco Bishop.

The course and character and result

of the Rebellion taught many a great new lesson; in political morals and in

political economy; in international law; in the theory of governing; in the

significance of just principles on this earth.

Perhaps all those lessons, taught so tremendously to the civilized

world, might be summed in one expression; the Astounding Strength of a

Christian Republic. For, whichever

phase of the Rebellion we examine in considering it as a chapter of novelties

in the world’s history, we still come back to that one splendid, heart-filling

remembrance;—How unexpected, how unbelieved, how inexhaustible, how magnificent

beyond all history, the strength of the United States!

“There goes your Model Republic,”

sneered all the Upper Classes of Europe, “knocked into splinters in the course

of one man’s life! A good

riddance!” And reactionary Europe set

instantly to work to league

[312]

itself with our own

traitors, now that the United States was dead, to bury it effectively. But the Imperial Republic, even more utterly

unconscious than its enemies, of what it could suffer and could do, stunned at

first and reeling under a blow the most tremendous ever aimed at any

government, clung close to Right and Justice, and rising in its own blood, went

down wounded as it was, into the thunder and the mingled blinding lightning and

darkness of the great conflict, unknowing and unfearing whether life or death

was close before. As its day, so was

its strength. As the nation’s need grew

deeper and more desperate, in like measure the nation’s courage, the conscious

calmness, the unmoved resolution, the knowledge of strength and wealth and

power, grew more high and strong, and whereas the world knew that no nation had

ever survived such an assault, and knew, it said, that ours would not, lo and

behold, the United States achieved things beyond all comparison more unheard

of, more wonderful, than even the treasonable explosion for whose deadly

catastrophe all the monarchists stood joyfully waiting. They were disappointed. And ever since, they know that if the

Rebellion was not the death-toll of Republics, it was the death-toll of many

other things, and ever since, all the kings are setting their houses in order.

There were three great national

material instrumentalities which the Free Christian People of the United States

created in their peril, being the sole means which could have won in the war,

and being moreover exactly the means which England and Europe asserted that we

were peculiarly unable to create or to use;

[313]

they were: the Supply of Money; the Army on the land,

and the Fleet on the sea.

Of these three, the story of the

fleet has a peculiar interest of its own.

The United States Navy was always a popular service in the country, for

the adventurous genius and inventive faculties of our people, developed and

stimulated by its successful prosecution of commerce, had easily dealt with the

naval problems of fifty years ago. In

the war of 1812, the superior skill of our shipbuilders and sailors launched

and navigated a small but swift and powerful and well managed navy, and the

single common-sense application of sights for aiming, to our ship-guns, in like

manner as to muskets, gave our sailors a murderous superiority in sea fights

which won us many a victory.

But in times of peace, a free nation

almost necessarily falls behind a standing army nation in respect of military

and naval mechanism and stored material and readiness of organization; and

accordingly, after forty years of little but disuse, our navy, as the muscles

of an arm shrink away if it is left unmoved, showed little of the latest

improvements in construction and armament, and indeed there was very little

navy to show at all. At Mr. Lincoln’s

inauguration, the whole navy of the United States consisted of seventy-six

vessels, carrying 1,783 guns; and of these, only twelve were within reach, so

effectively had Mr. Buchanan’s Secretary of the Navy, Toucey, dispersed them in

readiness for the secession schemes of his fellows in the cabinet. And even of those twelve, but a few were in

Northern ports. The navy conspirators

had no mind to have a southern blockade brought down on them, and so took

[314]

good care to send

our best ships on long fancy voyages to Japan or otherwise—and to clap on board

of them certain officers whose loyalty and ability they wished to put out of

the way. Thus General Ripley found

himself, to his indignation, over in Asia when the explosion took place.

It was from this beginning—practically

nothing—that the energy and skill of American inventors and seamen created a

navy beyond comparison the strongest on the face of the earth, reaching a

strength of 600 ships, and 51,000 men; which effectively maintained the most

immense and difficult blockade of history; which performed with brilliant and

glorious success, enterprises whose importance and danger are equal to any

chronicled in the wonderful annals of the sea; which fully completed its own

indispensable share in the work of subduing the rebellion; and which

revolutionized the theory and practice of naval warfare.

In this chapter of the history of

the navy the most famous name is that of Admiral Farragut, not so much in

consequence of any identification with the mechanical inventions of the day, as

because his past professional career and his recent brilliant and daring

victories, have linked together the elder with the younger fame of our navy,

and have done it by the exercise of professional and personal courage and

skill, rather than by the ingenious use of newly discovered scientific

auxiliaries. The hardy courage of

unmailed breasts always appeals more strongly to admiration and sympathy, than

that more thoughtful and doubtless wiser proceeding which would win fights from

behind invulnerable protections.

[315]

A friend of the writer was, during

the Rebellion, investigating some subject connected with the history of

medicine. In one of the books he

examined he found mention made of Charlemagne’s physician, a wonderfully skilful

and learned man, named Farraguth.

Our famous Admiral was then in the Gulf of Mexico, engaged in the

preparations for the attack on Mobile which took place during August of that

year. So odd was this coincidence, that

its discoverer wrote to the Admiral to ask whether he knew anything of this

mediaeval doctor, and received in reply a very friendly and agreeably written

letter, from which some extracts may here be given without any violation of

confidence, as giving the most authentic information about his ancestry.

“My own name is probably

Castilian. My grandfather came from

Ciudadela, in the island of Minorca. I

know nothing of the history of my family before they came to this country and

settled in Florida. You may remember

that in the 17th century, a colony settled there, and among them, I

believe, was my grandfather. My father

served through the war of Independence, and was at the battle of the

Cowpens. Judge Anderson, formerly

Comptroller of the Treasurer, has frequently told me that my father received his

majority from George Washington on the same day with himself; and his children

have always supposed that this promotion was for his good conduct in that

fight. Notwithstanding this statement *

* * * I have never been

able to find my father’s name in any list of the officers of the Revolution.

[316]

“With two men, Ogden and McKee, he

was afterwards one of the early settlers of Tennessee. Mr. McKee was a member of Congress from

Alabama, and once stopped in Norfolk, where I was then residing, on purpose, as

he said, to see me, as the son of his early friend. He said he had heard that I was “a chip of the old block”—what

sort of a block it was I know not. This

was thirty years ago. My father settled

twelve miles from Knoxville, at a place called Campbell’s Station, on the

river, where Burnside had his fight.

Thence we moved to the South, about the time of the Wilkinson and

Blennerhassett trouble. My father was then

appointed a master in the Navy, and sent to New Orleans in command of one of

the gunboats. Hence the impression that

I am a native of New Orleans. But all

my father’s children were born in Tennessee, and as I have said in answer to

enquiries on this subject, we only moved South to crush out a couple of

rebellions.

“My mother died of yellow fever the

first summer in New Orleans, and my father settled at Pascagoula, in

Mississippi. He continued to serve

throughout the ‘last war,’ and was at the battle of New Orleans, under

Commodore Paterson, though very infirm at that time. He died the following year, and my brothers and sisters married

in and about New Orleans, where their descendants still remain. *

* * *

“As to the name, Gen. Goicouria, a

Spanish hidalgo from Cuba, tells me it is Castilian, and is spelled in the same

way as the old physician’s—Farraguth.”

Admiral David Glascoe Farragut was

born at Campbell’s Station, in East Tennessee, in 1801. While only

[317]

a little boy, at

nine years of age, his father, who had been a friend and shipmate of the hardy

sea-king, Commodore Porter, procured him a midshipman’s berth under that

commander, and the boy, accompanying Porter in the romantic cruise of the

Essex, served a right desperate apprenticeship to his hazardous

profession. His first sea-fight was the

short fierce combat of Porter in the Essex, on April 13th, 1812,

with the English sloop-of-war, Alert.

No sooner did the Alert spy the Essex, than she ran confidently close

upon her broadside. Porter, not a whit

abashed, replied with such swift fury that the Englishman, smashed into

drowning helplessness, and the seven feet of water in his hold, struck his

colors in eight minutes, escaping out of the fight by surrender even more

hastily than he had gone into it.

In that desperate and bloody fight

in Valparaiso harbor, when the British captain Hillyar, with double the force

of the Essex, and by means of a most discreditable breach of the law of

neutrality, made an end of the Essex, Midshipman Farragut, twelve years of age,

stood by his commander to the very last.

When those who could swim ashore had been ordered overboard, Porter

himself, having helped work the few remaining guns that could be fired, hauled

down his flag, and surrendered the bloody wreck that was all he had left under

him, for the sake of the helpless wounded men who must have sunk along with

him. Farragut was wounded, and was sent